Imagine being told as a child in late 19th century Puerto Rico, that Black people had no history, no heroes, no memorable contributions. Like many Black and Brown folks, Arturo Schomburg recalls being told this all too well, and in his case, by his 5th grade teacher. The remarks coming from the “so called” educator infuriated him.

Born to a Black mother and German father, the incident fueled Schomburg’s lifelong quest to prove the instructor wrong.Today, Schomburg is remembered as one of the most important historians, scholars and essayists of the Harlem Renaissance — the black culture explosion that peaked around 1920. Schomburg was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on January 24, 1874, moved to Harlem in 1891. During his life in Harlem, his worked turned out exemplary for many intellectuals interested in the history of slavery and the West Indies, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library in Harlem is the most tangible evidence of his legacy.

“The Negro has been a man without history because he has been considered a man without a worthy culture,” he lamented in his influential 1925 essay, “The Negro Digs Up His Past.”

He succeeded in changing such perceptions through his writing and preservation of artifacts that could easily have evaded the public gaze, such as artwork and slave narratives. As described in the Atlas Obscura— Besides being an influential essayist, collector of slave memorabilia, Bibliophile, historian, scholar—the words that spring to mind when one hears Schomburg’s name have rarely included “gastronome.” Or what we call today Foodie..

But recipes were objects of scholarly obsession for him, too, where he located what he termed “Negro genius.”

Schomburg a renowned gourmet cook was a lover of good food. His passion for food was not to be taken lightly. Around 1930, just eight years before his death at 64, he began writing a cookbook, hoping to assemble 400 Afro-Atlantic recipes that showcased the breadth of Black ingenuity in the kitchen. He never finished it, and no one quite knows why. For decades, the proposal languished as it sat in the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.

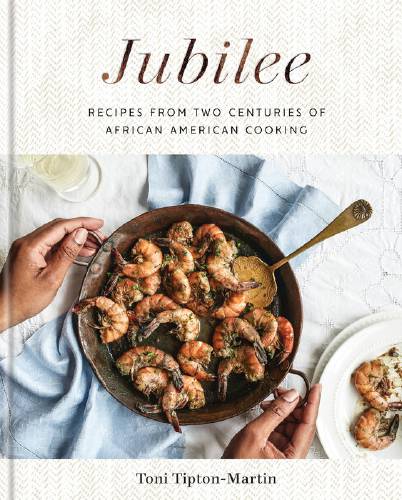

In the past year, though, the proposal has suddenly gained new visibility. Schomburg’s unfinished work formed the basis of two very different books published in 2019: Rafia Zafar’s Recipes for Respect: African American Meals and Meaning, and Toni Tipton-Martin’s Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking. The final chapter of Zafar’s book is a detailed dissection of Schomburg’s cookbook. In Jubilee, Tipton-Martin writes that Schomburg’s outline gave her “a blueprint of black culinary history,” using his recipe list as a map for her cookbook.

That the proposal is so crucial to two divergent works—Zafar’s book is a narrative nonfiction book, while Tipton-Martin’s is a cookbook—speaks to the enduring relevance of his vision. If America wasn’t quite primed to embrace a project of Schomburg’s ambition in the decades after his death, it certainly is now.

Schomburg listed out, one by one, hundreds of recipes that would populate his hypothetical cookbook. For breakfast, items such as kidney omelets, shrimp with hominy, or conserve of wild roses. Dinners of turtle soup, crawfish bisque, or squab pies. Suppers of grapefruit aspic with almonds, fresh fig ice cream, or pickled asparagus. Though Schomburg’s stated intentions were to include “various specialties from Haiti and the West Indies,” his recipe list skewed disproportionately towards his adoptive home of the United States, indicating that this recipe roadmap may not have matched his geographical aims.

These recipes would sit alongside biographical sketches of “famous Negro cooks,” though he also sought to highlight the “anonymous thousands” of brilliant cooks whose names no one else thought to record. His primary goal was to “show how the negro genius has adapted the English, French, Spanish and Colonial receipts taught him by his masters just as he adapted the stern Methodist hymns and the dour tenets of Protestantism—to his own temperamental needs,” he wrote.