AMERICA HAS always been full of languages, a fact that has been both a source of pride and a cause for consternation. But there has long been a fundamental misconception about one of its distinctive tongues: the speech of some of the country’s black population, especially in highly segregated areas. Not only is the nature of this dialect widely misapprehended; often its speakers are literally misunderstood by some of their fellow citizens.

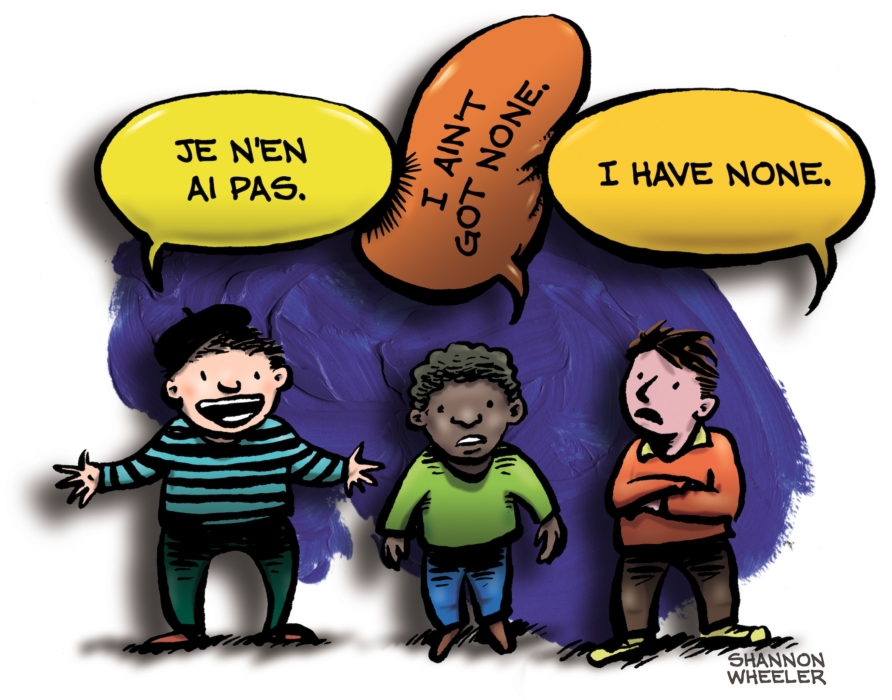

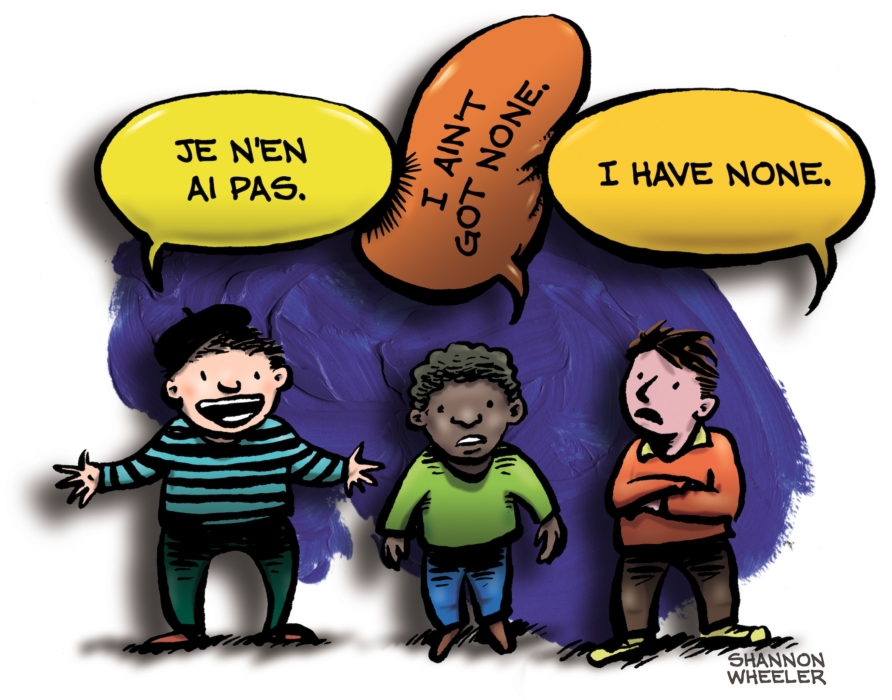

African-American English (AAE), is not a broken version of standard English, the mistake-filled attempts of someone trying and failing to talk correctly. Instead, it is like a cousin. It developed from the same roots, but in a different direction, born of unique circumstances. Enslaved people from various African backgrounds took what they learned of English and made it their own.

Centuries later, AAE is a rule-bound, internally consistent dialect. In some ways it is simpler than standard English. For example, it omits the –s on third-person singular verbs: I speak, you speak, she speak. But in some ways it is more complicated. She comin’ by my house means something different from She be comin’ by my house: the first is a one-off event, the second is habitual. I been did that means that I did something a long time ago. Standard English can achieve these effects with adverbs, but AAE integrates them into the verb system itself.

Misplaced snobbery about the nature of AAE is not the only problem. The dialect’s differences from the standard also lead to dangerous confusion. Taylor Jones, a graduate student in linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania, carried out a worrying study that found a group of professional court reporters were able to transcribe only 60% of AAE sentences accurately, and 83% of the words. Asked to paraphrase what they had heard, they did even worse: about 33% of utterances were conveyed accurately. They are supposed to achieve a 95% accuracy.

Experienced court reporters did no better than newer ones, and black reporters little better than the white ones. Black participants explained their trouble with AAE by saying that they (like many other African-Americans) didn’t “speak like that”. Worse, both black and white court reporters tended to assume the recordings were from criminal court (they weren’t). That people associate AAE with ignorance and criminality is bad enough. Misunderstanding aggravates the risk. No one can get justice from a court that doesn’t know what they are saying.

The miscommunication runs both ways. Adult black Americans who use AAE can easily understand standard English, from exposure in school, work and the media. But youngsters from homes and neighbourhoods where AAE predominates are a different matter. In another study, Mike Terry of the University of North Carolina tested AAE speakers in second grade (roughly 7 years old) on their maths. He found that questions including the third-person-singular ending –s (he talks, which in AAE is he talk) made the students 10% less likely to answer correctly. Language is not just language; it is the interface with other kinds of knowledge. Such pupils are being judged as less capable than they really are.

A close linguistic analogy to AAE is Scots, which differs from standard English to a similar extent. In its full form, it is at least as hard for outsiders to understand. But in policymaking terms, it is not a useful comparator. Scots have a homeland and a nationalist movement; they are not generally the subject of disparaging prejudice.

It may be better to think of AAE as posing the same challenges as a foreign language, albeit in diluted form. Seeing the problems some of its speakers face as essentially ones of translation might let policymakers appreciate and solve them. This does not mean providing courtroom interpreters for black speakers, or classes taught in AAE. It means training court staff or teachers in the issues involved.

America is a diverse place, and standard English is part of the glue that holds it together. All the more reason to take a linguistically informed approach to teaching it. For example, classroom exercises similar to “translation” from AAE to standard English can help children master the standard, in a way that shaming them for “mistakes” (in fact, correct AAE) does not. The standard is not the only kind of English there is. Paradoxical as it may seem, recognising this linguistic diversity will help a divided country approach the ideal of its motto: e pluribus unum.

Source: https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2019/04/12/how-to-think-about-african-american-english