That’s easy, I’m a descendant of slaves. I’m African American. And, my Texas roots run deep.

Although I was born in Arizona, Texas, is where it all started for me. My maternal and paternal family members were sharecroppers that picked cotton throughout the lone star state, settling in cities like Austin, Crockett, Dallas, Houston, Taylor and more of the small rural places in what we call “country towns,” that are spread out along the Texas highways. Many of my family members left Texas, for Arizona, during the 1940s after learning that a cotton pickers pay was much better— 75 cents a bale in comparison to Texas, which was barely nothing. Slave labor indeed.

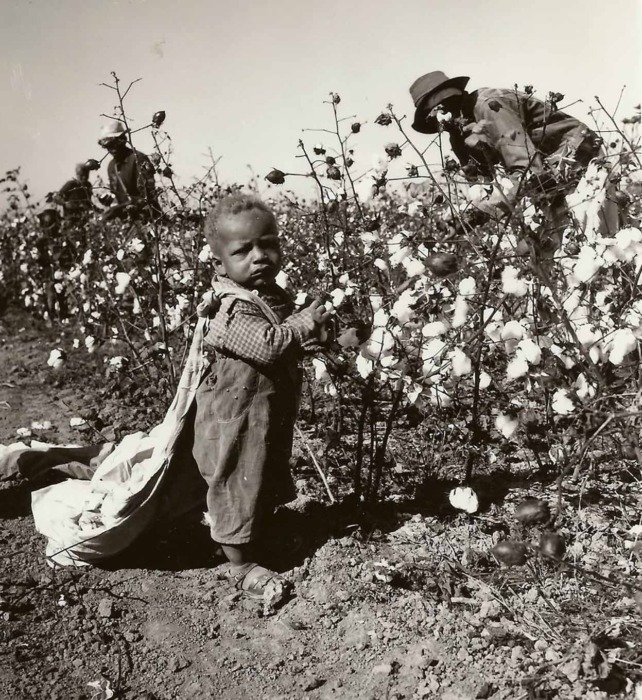

I was told by my mother that she started picking cotton at THREE YEARS OLD!

My mom’s mother, who just happened to be born on June 19 (Rest in Heaven Grandma Willie Mae), passed away when my mom was just twelve. My grandfather Henry, both of his parents were slaves, decided to leave Austin Texas, temporarily, with plans to return to Texas, taking my mom, and her younger sister with him to pick cotton in Arizona. My grandfather eventually returned to Texas.

They ended up settling in a small town called Marana, just outside of Tucson. In Marana, during the forties and fifties, Black folks, that migrated from different places mostly Texas, bonded and became as close as family while working the cotton fields. They went on to create businesses, church communities, and found work, all the while holding on to their southern ways and Texas roots.

From what I was told, most people who migrated to Arizona are from East Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana.

Here’s what Juneteenth means to me. As I recall, my first Juneteenth celebration was during the early seventies. Our small community of less than one percent Black at that particular time, would gather at a park on “A” Mountain, in Tucson. And it was always held at that one location. I’m sure that it’s changed locations over the years but, at that time that location was perfect.

Stages were set up where local bands, church choirs, vocalists, fashion shows and anyone who wanted to present their talent from the community came out to entertain and celebrate the community.

It was always a great turnout! It felt like a big family reunion, with extended family–cousins everybody Black came out. There was so much pride and unity in our small, tight-nit community. Every year we managed to come together in the extremely hot desert town, to celebrate our rich Black culture.

This year due to the pandemic, Juneteenth in Tucson was a virtual event.

Side note: I can’t tell ya’ll how many times (mostly Black) people would say to me when I tell I’m from Arizona, they would say—“ It’s too hot over there! I didn’t know black folks lived out there!”

Ya’ll just don’t know how bad I wanted say back , ‘hello, don’t forget Africa, the continent where we all came from is hotter than Arizona!’

https://thechocolatevoice.com/juneteenth-in-san-diego/Juneteenth in San Diego, CA

Juneteenth Celebration in Los Angeles

For full disclosure, as a young girl growing up in the AZ, I really wasn’t fully aware of the history behind Juneteenth. It certainly wasn’t taught in schools. All I knew was that I looked forward to the annual event that took place during the hottest time of the summer. It would get as hot as 118 degrees sometimes. But, I didn’t mind as long as I could come to a place where all of Black Tucson with Texas roots gathered to celebrate Juneteenth.

And, let’s not forget the food—Barbecue chicken, ribs, hot links, potato salad, greens, pound cakes, banana pudding, sweet potato pies, black-eyed peas, corn bread, watermelon, you name it. Just so you know, Black folks in Arizona can cook too!

So, the history behind Juneteenth is that it’s derived from the order that Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger read on June 19, 1865, in the District of Texas headquarters in Galveston. But the Emancipation Proclamation ostensibly ended slavery 2 1/2 years before that.

For many Texans, particularly in the Houston-Galveston region, Galveston, being one of the largest cotton shipping ports in the world during the mid-19th century, is where Granger arrived with 1,800 Union troops on June 19, 1865, carrying General Order No. 3, advising that all slaves had been declared free.

Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation on Sept. 22, 1862, but slaves in Texas remained enslaved until Granger’s Union Army arrived to enforce it.

When black people in Texas finally received the news that our people were free, two years later, spontaneous celebration erupted throughout the slave communities, Juneteenth became a freedom day celebration, expressing African pride, solidarity and cultural tradition.

With all that’s going on with Black Lives Matter protests, and for those who that are just know learning about Juneteenth, I’m thrilled that the meaning of Juneteenth has forced people to really think about the long history of colonization and racism in this country. Sadly, it took the recent deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and now Rayshard Brooks that have forced people to connect with Black Lives Matter activism.

2020 has been some kinda year. Who would have thought that National companies would recognize Juneteenth as a paid holiday, and that it has become apart the conversation that’s relevant to today’s political moment and at the center of activism.

Reflecting on my experience as a child celebrating Juneteenth, I’m glad that my Texas roots is a reminder of America, and her complicated past with race relations and enslavement.

Gwen